Spring 2019

From the Archives

An excerpt from NPCA’s first newsletter.

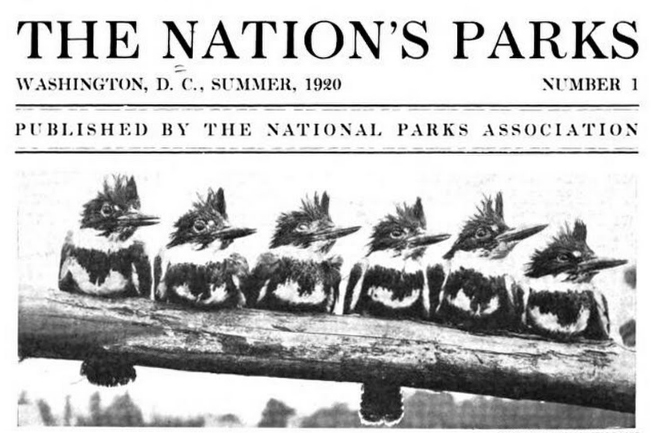

Issue No. 1 of “The Nation’s Parks” was published by what was then called the National Parks Association in the summer of 1920. Single copies, prepaid, were 10 cents each. The 16-page newsletter opened with a photograph of belted kingfishers at Yellowstone Lake and the headline, “Hands Off the National Parks.” Here, we reprint an essay from the issue by co-founder and Executive Secretary Robert Sterling Yard introducing the association and its mission to readers. Though a second issue never materialized, the newsletter was a precursor of what became National Parks magazine in 1942.

Salutamus

This is the first number of an illustrated news sheet in the interest of National Parks and Monuments of the United States. It is issued by an association of citizens which seeks the finest possible upbuilding of a system destined to become one of our most valuable economic assets, and to promote the widest possible uses of the parks by all the people.

The Association’s work does not overlap that of the Department of the Interior; it begins where the Governmental function ceases, for Congress provides only for the physical development of our National Parks. Their enormous value to popular education, to the increased pleasure which comes only with understanding, to outdoor living and to travel in America is left for the people to develop. It is to help reap this important harvest and to bring together in a common endeavor the helpful citizens of every part of the land that the National Parks Association was founded.

Its opportunity, however, is much greater, and the Association is availing of this to the full. Unconnected with the Government and absolutely independent of political or other adverse influences, it has become the fearless and outspoken defender of the people’s parks and the wild life within them against the constant, and just now the very dangerous, assaults of commercial interests.

The Meaning of Scenery

Those several thousand Americans who saw Sarah Bernhardt act without understanding her spoken word got pleasure and profit from the contemplation of her supreme art, but in no proportion with those who also understood her language. Similarly many hundred of thousands of summer travelers find pleasure and profit in our National Parks, who are robbed of their higher pleasure by failure to understand nature’s simple language.

The simile goes much farther, for millions of Americans who have not yet visited the National Parks and may never visit them find keen pleasure in the photographs and paintings of these masterpieces of nature and in the written descriptions of their wonders. For these, too, the pleasure would be many fold increased by the knowledge of what they mean in nature’s complicated plan; for after all the great places are great principally because they exhibit in gigantic outline the working of the same laws which apply also to the earth’s entire surface.

The wayside ditch in Illinois, for instance, and the Grand Canyon are precisely the same in the making; the low rounded summits of Maine were once splintered and glaciered like the lofty Sierra of today in obedience to the identical law; the glowing wild-flowered basins at the Rockies’ feet were spread in response to the same command which produced the plains of our Central and Eastern States.

Our National Parks, then, are the easy and fascinating charts to a comprehension which will remake this whole land of ours into a thing of supreme interest. Understand them, whether by visit or in picture, and every simple landscape the country over becomes charged with meaning; our walks, our drives, our motorings, our vacation sojournings, no matter where, assume a significance and an intimacy they never before possessed. Gradually, but swiftly, everything upon which the eye rests leaps into its place in nature’s great plan. The insignificant becomes the important, the homely becomes the beautiful. We find a pleasure in the cracks and seams of rocks because now they speak to us; also in tiny brooks, in ridges, in insignificant valleys, in plant differences resulting from environment, in bird and animal and even reptile life. Instinctively we sort and classify and place. We are impatient to get home to consult our books and again impatient to return to our discoveries.

This we may call one of the several higher uses of the National Parks — of the National Parks especially because the glory of their scenery attracts and holds all eyes. The sated traveler here starts in astonishment. The man or woman absorbed in affairs achieves a new and intense interest. Here nature’s story is written in characters of sublimity. How, why, are the words which spring to every lip. And the how and the why of these spectacles are the how and the why of the merely commonplace everywhere; only now no longer to be commonplace.

One of the reasons for the founding of the National Parks Association was to realize this higher use of the National Parks. If, with the help of cooperating Government bureaus, universities and schools, it succeeds in bringing home to some part of the people the beauty and significance with which their land is saturated, it will have justified its labors.

But mark this. It is to no study of abstruse science that we invite you. It is not necessary to become a geologist or a botanist or a zoologist to penetrate Nature’s secrets, nor to tell schists from granites, classify the conifers or call a bird by its Latin name. A few popular books, many pictures carefully studied and a sincere desire will open the window upon an old world made new.

Your Part

It is the duty of every man and woman who wants to see those magnificent national museums of native America, our national parks, preserved from commercialism for posterity, to write so to his Senator and Representative. Otherwise, in these days of strenuous issues, the best-meaning Congressmen — they are all overworked — will not appreciate the strength of the national feeling in this hour of peril.

About the author

-

Robert Sterling Yard Founder/Editor

Robert Sterling Yard Founder/EditorRobert Sterling Yard, a former newspaper reporter and gifted wordsmith, honed his skills as a newsman and writer in the journalism trenches of Manhattan. He became executive secretary of the National Parks Association in 1919.