Winter 2021

Circling the Mountain

Another season, another ceremonial circumambulation of Mount Tamalpais. What draws hikers to this 55-year-old ritual?

December 22, the day appointed for our hike around Mount Tamalpais, did not look at all promising. Temperatures were in the 40s, the wind was up, and the brooding dawn sky looked like it held enough water to rain all day. After parking near the starting point of the hike in Muir Woods National Monument, on the Marin Peninsula north of San Francisco, I wrangled foul-weather gear in the cab of my truck in the dim light as rain began to hammer the roof of the pickup and surrounded it in swirling curtains. Through the deluge I could just make out a doe and fawn, patiently browsing weeds along the fringe of the empty parking lot.

Eventually, a few intrepid walkers appeared, arriving late because the torrential rain had joined a king tide to flood a highway offramp, necessitating a detour. As our little group of seven huddled together, Laura Pettibone, our hike leader, explained over the dull roar of the downpour that at winter solstice the 15-mile route around the mountain is difficult to complete before dark and that it would be especially challenging today, given the miserable weather and our late start. “But that’s the Zen of this hike,” she said, smiling as raindrops splashed on her cheekbones. “You never know what the weather will do or how your body will do.” She pulled a laminated sheet of text from beneath her bright yellow rain poncho and began chanting, in Japanese, a Mahayana Buddhist text called “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra.” After completing the mesmerizing chant and tucking the sheet back inside her raingear, Pettibone reminded us that we would be hiking in silence during the ascent, which would mean I would be spending the better part of the day with only the quiet of my thoughts and the sounds of wind and rain.

In circling the mountain, we would be repeating a ceremony that has been performed for 55 years. On the morning of October 22, 1965, the Beat Generation poets Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg and Philip Whalen stood near this spot and chanted the Heart Sutra before setting out to consecrate the mountain through ritual circumambulation. That historic walk would be enshrined in Snyder’s poem “The Circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais” and Whalen’s poem “Opening the Mountain, Tamalpais: 22:x:65.” The first lines of Snyder’s poem introduce the story: “Walking up and around the long ridge of Tamalpais, ‘Bay Mountain,’ circling and climbing — chanting — to show respect and to clarify the mind. Philip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg, and I learned this practice in Asia. So we opened a route around Tam. It takes a day.”

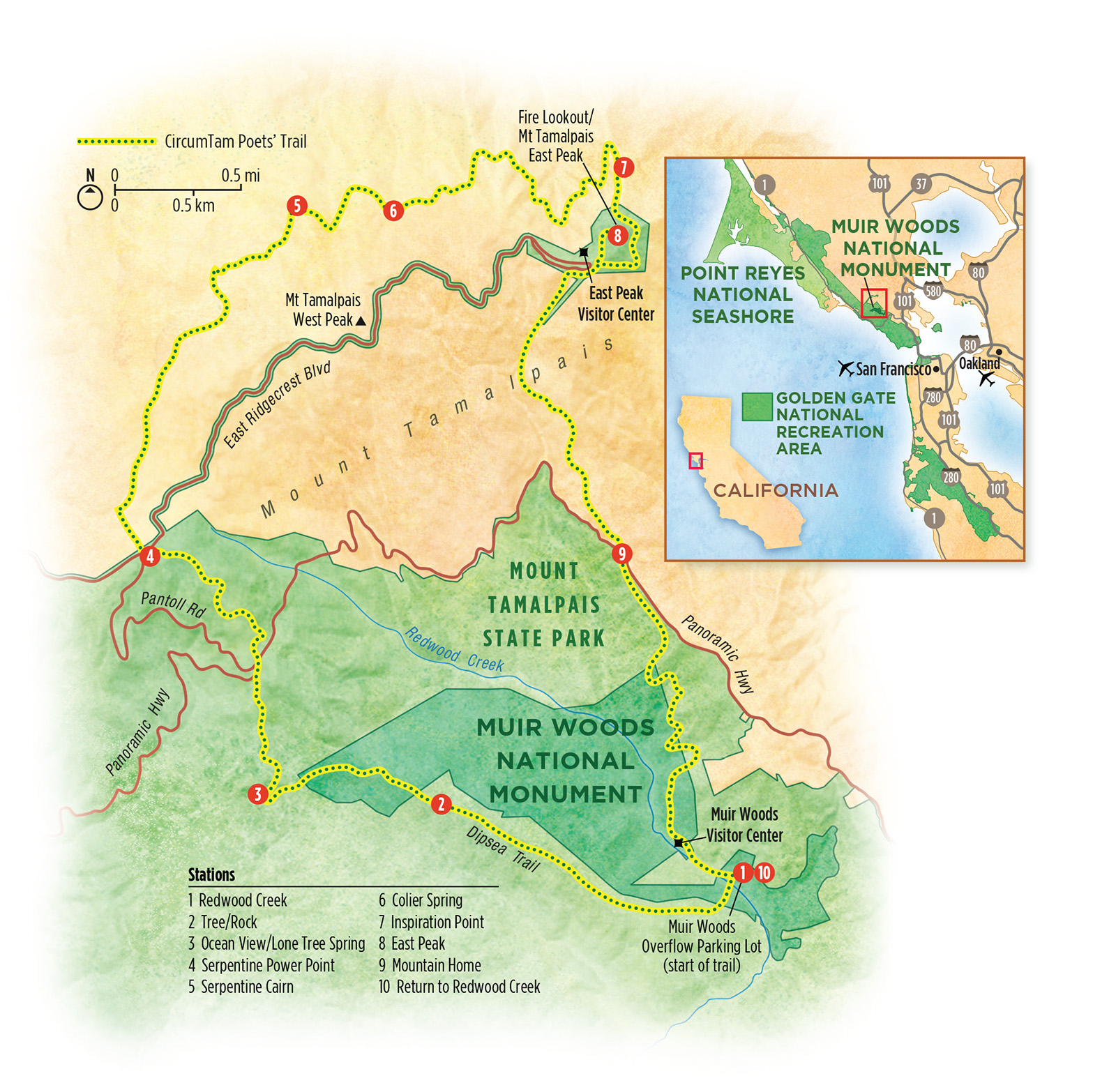

He would later explain his motivation for pioneering the ritual walk: “I felt it was time to take not just another hike on Mt. Tam, the guardian peak for the Bay and for the City — as I had done so many times — but to do it with the intent of circling it, going over it, and doing it with the formality and respect I had seen mountain walks given in Asia.” Starting at Redwood Creek in Muir Woods, the three Beat poets walked clockwise around the mountain, stopping to chant at 10 “stations” — notable spots along the route that were selected spontaneously for what the poets considered their special power — before closing the loop back at the creek.

In San Francisco’s countercultural community, word spread that the poets had completed a ceremonial walk around Mount Tam, and admirers soon committed to perpetuating the ritual. An open invitation to circle the mountain on Feb. 10, 1967, appeared in a Haight-Ashbury newspaper, and fliers announcing the hike were posted along Haight Street. Led by Snyder, that first public circumambulation replicated the original circuit. A group of around 70 circled the mountain together, stopped at the established stations, and performed many of the same chants.

By 1972, the ritual circumambulation was performed four times each year, on the Sunday closest to the dates of the solstices and equinoxes. For more than 40 years, this ceremonial walk was led by Matthew Davis, a local hiker and admirer of Snyder, who had attended the original group walk and went on to finish the route at least 160 times. After Davis died in August 2015, his son took over for a couple years, before Pettibone, Davis’ protegee, picked up the mantle. She has now circumambulated the mountain more than 100 times.

Ritual circumambulation has its origins in a number of spiritual traditions. For Snyder, Ginsberg and Whalen, all of whom were practicing Buddhists, the source of the tradition was Zen. Snyder made his first trip to Japan in 1956, and while studying at a temple in Kyoto, he was introduced to a form of walking meditation often performed on nearby Mount Hiei. The circumambulatory practice, called “pradakshina” (Sanskrit for “the path surrounding something” or “to the right” depending on the source), is a religious rite that involves circling a sacred object (a temple, a gravesite, a mountain) in a clockwise direction to absorb spiritual energy or power from it. The ritual, which Japanese Buddhist monks still practice, evolved from ancient forms of walking practice originating in China and India.

Gary Snyder in 1964. The three poets circumambulated Mount Tam in 1965, establishing a ritual that has endured.

© LAVERNE HARRELL CLARK/THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER, 1964Snyder knew Mount Tamalpais well by 1965. His first trip to the mountain was in the summer of 1939, when he was just 9 years old. In 1948, he shared a memorable three-day hike there with his first love. In the years following his move to the Bay Area in 1952, Snyder walked Mount Tam often, and in 1956, he took up residence in a shack on the mountain’s flank. That cabin, which he called Marin-an, became an improvised zendo and a creative hub for Beat poets and writers. For a time, Snyder’s friend Jack Kerouac lived with him in the shack, a barely fictionalized version of which appears in Kerouac’s 1958 novel “The Dharma Bums.” Among Snyder and Kerouac’s guests at Marin-an were Ginsberg, Whalen, Neal Cassady, Kenneth Rexroth, William Burroughs, Lew Welch and Gregory Corso. Of this remarkable group of countercultural figures, only Snyder, who is now 90, is still alive.

By the time Snyder, Ginsberg and Whalen circled Tamalpais (whose name likely comes from the Coast Miwok “támal pájis,” roughly meaning “west hill”), the mountain had long been a site of recreation and inspiration. Preservationist John Muir hiked Mount Tam, as did photographer Ansel Adams, painter Maynard Dixon, suffragist Alice Paul and many other luminaries. The early 20th-century struggle to save the mountain as a natural space with public access had its roots in the advocacy efforts of the 19th-century hiking clubs that frequented Mount Tam. The mountain today is a patchwork of private, municipal, county, state park and national park lands that includes Muir Woods National Monument and parts of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

My first opportunity to complete the “CircumTam,” as it is sometimes called, came in 2004, when several friends of Snyder’s invited me to join them on the walk. I had long admired Snyder’s writing and had been profoundly influenced by “The Practice of the Wild,” his 1990 book of essays exploring the biological, social and spiritual value of wild landscapes. Our leaders that day were a pair of talented writers and photographers: my friend Sean O’Grady and his mentor David Robertson, then a colleague of Snyder’s at the University of California, Davis. A scholar of literature and religion who has studied and written about circumambulatory practice, Robertson believes that the heart of circumambulation is ritual, which provides structure and meaning in a world that might otherwise feel chaotic. “Ritual puts our own situation in a larger context,” Robertson told me during a recent conversation. “The ritual of circumambulation is about transferring some kind of meaningful power from the land to yourself.”

I experienced a sense of that transfer of power on my first CircumTam. In addition to being awed by the beauty of the mountain, I felt a deep connection to the friends I spent that day with, and I was moved by the idea that the walk itself was a kind of literary product — one that had led to a shared experience of this special place that continues to unspool over time. During the next 16 years, I completed the hike a half-dozen times, always traveling with companions who, like myself, are environmental writers. However, I was aware that for a half-century, a group of hikers had been regularly performing the circumambulation in a more structured way. While my hikes had included stops at the stations identified in the Snyder and Whalen poems, I was interested in this group’s deliberate practice of conducting the hike just as Snyder and his friends had in 1965, Buddhist chants and all. My inquiries with rangers at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area led me to Pettibone, who was gracious and welcoming, and plans were soon made for me to join the winter solstice walk.

A flock of nonnative wild turkeys strutted past as Pettibone led our group on the first steps of our journey. Foregoing Redwood Creek, uncrossable because its modest plank bridge had been removed to allow salmon to reach their spawning grounds, we instead climbed a fire road to intersect the celebrated Dipsea Trail. But the trail had played trickster by turning itself into a creek, its shallow banks overflowing as we worked our way along — and sometimes through — the ephemeral stream. We soon rose out of the redwoods into a forest of Douglas firs and California bay laurels, which give much of this hike a distinctive peppery aroma — though Snyder noted in his poem that Ginsberg thought the laurels smelled like fried chicken. Although the trail meandered through a gorgeous mixed conifer forest, I was unable to achieve anything remotely resembling a Zen state of mind. Soaked through from head to toe after a single mile, I instead meditated on the likelihood of hypothermia should we press on for another eight or 10 hours under such adverse conditions. I wondered, in fact, if we might be endangered by our zeal to honor the ritual.

Pushing ahead despite my trepidation, I felt the path ascending from the wet, green bower of Redwood Creek to the exposed southern flank of the ridge, where a tenacious coast live oak dramatically splits a giant, lichen-splattered boulder. This was the same tree, the same rock the Beat poets had consecrated on their 1965 walk. In his poem, Whalen’s austere language expresses the beauty of the site: “Oak tree grows out of rock / Field of Lazuli Buntings, crow song.” As I watched Pettibone offer a small bow of respect to what circumambulators, with Zen-like clarity, often call Tree/Rock, I wondered what it takes to sanctify a place. This tree and rock, so perfectly natural, have become part of a rich and now intergenerational cultural fabric. A half-century of mountain pilgrims have rendered this place a shrine; and yet, it remains a tree, a rock.

By the time we approached the station called Serpentine Power Point, the rain had let up, but the cold had settled in, and the numbness in my fingers and toes had me flexing and stamping to maintain sensation. I glanced occasionally at my fellow hikers, trying to assess whether the piercing cold had numbed them as well. We stopped amid a spectacular outcropping of serpentine, a crest of angular but smooth-faced, blue-green boulders. In the rich lore of the Tam circumambulation, this site is often referred to as “the spiritual driver’s seat of San Francisco,” a power spot even among power spots. Geologically, the place might well be considered special, given that serpentine (the state rock of California) typically forms deep within the Earth at the boundaries of grinding tectonic plates. Scientists are uncertain how it makes its way to mountaintops, though they hypothesize that because serpentine is remarkably malleable, it is squeezed to the surface along the unstable fault lines where it is often produced.

A few more miles brought us to our lunch spot at the Rifle Camp picnic grounds, where photographer Philip Pacheco — whose images grace this essay — generously shared with me his Korean kimbap, a sliced roll with seaweed, rice, fish cake, carrots, spinach, yellow pickled daikon and egg. According to Snyder’s poem, the poets’ spread in 1965 wasn’t bad either: Along with Swiss cheese sandwiches and salami, they also shared gomoku-no-moto, panettone with apple-currant jelly and sweet butter, and Greek walnuts in grape juice paste.

Fortified, we set out for the north side of the mountain, which was deeply shadowed, but also protected from the winds that had cut into us on the ocean side of the hike. Redwoods gave way to the naked, spiraling musculature of madrone trees; other trees were so completely covered with small ferns that their bark remained hidden beneath the shimmering verdure encircling them. On this wind-sheltered side of the mountain, silence prevailed, allowing details to come into sharp focus: the trickling of water echoing in a mossy glen; the iridescence of rain droplets globed on the bony fingertips of twigs.

A notable cairn of rocks (permitted by a benevolent private landowner) comprises the fifth station of the ritual walk. Each hiker brings a single stone — carried from as close by as a few feet or as far away as another continent — and adds it to the cairn. My offering was a rough oval of blue granite the size of a wild cherry, which had come with me from my home in the Great Basin Desert on the Nevada side of the Sierra crest. Having ceremonially laid our rocks atop the pile, we walked around the cairn clockwise, each of us both leading and following as we traced the small circle of this moment within the larger circle of the day and the yet more expansive circles of the season and the year.

As our ascent toward Mount Tam’s East Peak began in earnest, a break in the clouds revealed the landmark fire lookout, perched like a ceremonial teahouse atop the distant summit. A little farther on, at Inspiration Point, the clearing weather opened a spectacular view: up the rippled hills toward Napa Valley; out over the colonnaded fortress of San Quentin prison and the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge; and, all the way to the needled skyline of downtown Oakland. The respite from rain and wind also brought welcome warmth, the return of sensation to my fingers and toes, and a new hope that we might dry out before the sun set.

At the foot of the final ascent, we huddled together, by necessity breaking our silence to confer. With some regret, we quickly reached consensus that the waning light of this short, winter day would not allow us to add the sacred mountain’s summit to our route, as we had hoped.

“That’s OK,” said one of the hikers, Nick Triolo. “I’d rather not make the summit push anyhow. Best to leave that for coyote.” In the culture of the Coast Miwok, summiting a mountain risks disturbing its peak-dwelling spirit — which, in the case of Mount Tam, is believed to be coyote, he said. In any case, circumambulation doesn’t have a summit-driven “conquering sort of intention,” he added. “At its core, a circular walk in a landscape is contemplative, investigative, surveilling a place with a deep scrutiny of all its sides.” Triolo, an online editor at Orion Magazine, had grown up in the Bay Area but had learned of the circumambulatory practice of “kora” while on a trip to Nepal. Inspired by that experience, he began to study circumambulation in various cultural traditions, and now he had returned to Northern California from his home in Massachusetts to perform the ritual on Mount Tam.

After a long day of climbing and traversing, our descent at last began — and, with it, lots of free-flowing conversation. There was talk of hot coffee and cold beer, of baseball and poetry, of travels on mountains near and far. I appreciated the way the silent hike had provided me the opportunity to focus on what I felt, saw and heard. But I had also developed a genuine sense of camaraderie with my fellow hikers, despite the absence of small talk and the fact that I knew almost nothing about them. Miles of walking and shivering together had forged a bond I think the Beat poets would have appreciated.

The descent was my opportunity to learn more about what brought these former strangers together on the mountain. Without exception, everyone commented on the value of ritual. Lisa Kadyk, a geneticist, said, “I’m not religious, but I do like rituals and recognition of spirituality in a big sense.” Visual artist and environmental field educator Kerri Rosenstein put it this way: “I like the nature of practice. To do something over and over. To train. It requires patience and discipline. I trust that each time offers something new. That we evolve by repeating the same walk as we awaken both to what becomes familiar and to what becomes revealed.” Gifford Hartman had throughout the day played the important role of “sweep,” following us to make certain no one took a wrong turn or needed help. “A ritual is returning to a place,” said Hartman, an English as a second language instructor. “Rituals also reinforce the seasonal cycles of life.”

Like me, some hikers had been attracted to the CircumTam through literature or art. Hartman had been inspired by the Beat poets, especially Snyder, whose work he had loved as a young man. After moving to the Bay Area, he had been drawn to Mount Tam not through religious practice or friends, but rather through the Snyder and Whalen poems documenting the circumambulation. The natural beauty of this mountain had inspired that first ritual walk in 1965. The walk had inspired the poems. For Hartman, the poems had then inspired the walk, just as the poets intended. As Snyder explained in a 1989 interview with David Robertson, “I thought I would consecrate Tamalpais as a sacred mountain for future generations to do the same kind of pilgrimage on.”

Hartman then articulated an insight I had been struggling toward. While celebrated nature writers such as Muir deified wilderness, the Beats had deliberately chosen to consecrate a well-traveled mountain that stands shoulder to shoulder with one of the world’s great cities. They had intentionally brought culture — in the form of spiritual practice and literary performance — to their understanding of why and how nature matters. By sanctifying Mount Tam in the way they did, Snyder and his fellow poets encouraged us to move beyond a rigid conceptualization of nature and culture as binary realms. The ritual the Beats forged on Mount Tam, Hartman said, “is part of a legacy of bringing the human world into the natural world.”

The sun struggled to find openings in the darkening sky as we continued our descent. We followed the Fern Canyon Trail as it dropped steeply through an impossibly green valley on the mountain’s south face, where manzanita, ceanothus and coyote brush dominate the landscape. From one spot, we picked up an exhilarating view of the spires of the San Francisco skyline.

The Canopy View Trail would take us the rest of the way home to Muir Woods and Redwood Creek. But we still had more than an hour of hiking ahead as we watched the last shafts of sunlight retreat beyond the horizon ridge, and we had to decide whether to take our chances walking in the dark or instead navigate by the beams of our headlamps. After a quick conference in the falling dusk, we agreed to complete the circuit by starlight and proceeded single file down into the redwoods.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Snyder’s poem describes this last leg of the sacred walk as “The long descending trail into shadowy giant redwood trees.” Seeds only an eighth of an inch long had produced these coast redwoods, some of which have trunks a dozen feet in diameter and crowns reaching an unfathomable 200 feet into the night sky. Sauntering through the silent forest, I thought about the years that had elapsed between the Snyder-Ginsberg-Whalen circumambulation and our own, and I compared that span to the lifetimes of the venerable trees I walked among, some of which have stood fast 20 times longer than the brief half-century pilgrims have been circling this mountain.

The tenth and final station of the circumambulation is also its first station. I had a feeling that, just as the Beat poets intended, this arrival would become a new point of departure. Approaching the CircumTam’s beginning-end, I remembered the good friends who first guided me on this mountain so long ago. I thought also of my daughters, who will soon be strong enough to join me on the demanding and rewarding ritual walk. This stormy, nine-hour circuit of the mountain had become a circle within the larger circles of seasons and years that also encircle our own short lives.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Footsore but content, we seven hikers paused by Redwood Creek and exchanged hugs, saying goodbye to each other and to the day. Several in our group suddenly exclaimed, as above the dark forest canopy westward toward the sea, a meteor ignited, its tail tracing a bridge of light across the sky.

About the author

-

Michael P. Branch

Michael P. BranchMichael P. Branch has published nine books, including three works of humorous creative nonfiction inspired by the Great Basin Desert: “Raising Wild” (2016), “Rants from the Hill” (2017) and “How to Cuss in Western” (2018). His essays have appeared in venues including Orion, CNN, Slate, Outside, Pacific Standard, Utne Reader, Ecotone, High Country News, Terrain.org, Places Journal, Whole Terrain and About Place. He is University Foundation Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno. His new book, "On the Trail of the Jackalope," will be published by Pegasus Books in 2022.