Summer 2021

Miners' Angel

A century ago, Mother Jones faced bullets and long odds in her quest to better the lives of coal laborers working in New River Gorge and other West Virginia mines.

Union organizers told Mother Jones not to go to the coal mines on Laurel Creek. The strikes that started in West Virginia in June of 1902 had dragged on for months, and mine owners had only gotten more combative as time passed. In their attempt to unionize miners, the seven organizers had been beaten up and shot at, and gunmen hired by the mine operators were patrolling the access roads, ready to shoot any intruders on sight. This gave the grandmotherly activist all the more reason to hike the 6 miles of rough terrain separating Thayer, deep in New River Gorge, from the Laurel Creek mines. “That means the miners up there are prisoners and need me,” she said.

From 1897 until the mid-1910s, Mother Jones returned time and again to unionize laborers in the mines located in what is now New River Gorge National Park and Preserve and other coal fields of West Virginia and help improve their working conditions. During a labor conflict that has been described as the largest U.S.-based insurrection outside the Civil War, she faced bullets and thugs and endured military trials and imprisonment. For weeks on end, she would crisscross the rugged countryside — often at night to avoid detection — to reach remote mining camps. And she did it all in her 60s and 70s.

“It takes such a dogged and persistent person to do this day after day after day,” said Catherine Moore, the president of the board of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. “She was kind of a badass.”

Mother Jones on September 26, 1924, when she met President Calvin Coolidge at the White House in Washington, D.C. She was likely 87 years old at the time.

UNDERWOOD ARCHIVES/LIBRARY OF CONGRESSAfter spending the first six decades of her life in relative obscurity, Mary Harris Jones engineered a remarkable second act and became one of the most famous women in the country, known to her friends and enemies alike simply as Mother Jones. Defying prevalent gender norms, she butted heads and negotiated with the most powerful men of her time, including President Woodrow Wilson and business magnate John D. Rockefeller. But it is among the working class that she achieved iconic status, delivering electrifying and profanity-filled speeches that helped inspire “her boys” to fight for workplace rights and put the powerful on notice. In a 1912 address to West Virginia miners, she described the state’s governor as a “goddamned dirty coward” and warned “this little governor” that if he didn’t get rid of the mines’ armed guards, “there is going to be one hell of a lot of bloodletting in these hills.”

Mary Harris was born in Cork City, Ireland, likely in 1837, just a few years before a potato blight caused widespread famine and prompted more than 1 million people to leave their country. Harris’ family emigrated to North America and settled in Toronto, where the young Mary eventually attended a school for teachers. She never graduated but still landed a teaching job in Monroe, Michigan, in 1859. Later, she worked as a dressmaker in Chicago, and in 1861, she married George Jones, a unionized iron worker, in Memphis. Mary Jones built her own family there, but it was all taken away from her by a yellow fever outbreak that tore through the city in 1867. One by one, her four young children and her husband died. Jones decided to rebuild her life in Chicago and return to dressmaking, but again, disaster struck when her shop and possessions were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

“She does have this terribly tragic life, literally of famine, pestilence and fire,” said Elliott J. Gorn, the author of a biography of Mother Jones.

It’s unclear exactly what prompted Jones to become involved in the labor movement, but she soon dedicated herself to union work. She seemed to materialize every time a conflict arose between workers and employers, joining railroad, steel and textile workers in their efforts to improve their lot. She recruited union members, confronted bosses and garnered publicity for the plight of the workers, who considered her a savior of sorts — an elderly but vigorous Joan of Arc for the industrial age.

It was in the coal fields of West Virginia that Mother Jones waged her longest-running battle. Pay there was lower than in the coal mines of the Midwest; miners, who were compensated by weight of coal extracted, were often cheated at the scales; and the mining companies, which ran the stores, charged exorbitant prices. As a result of looser regulations, the work there was also more dangerous than at coal mines elsewhere in the country. The United Mine Workers of America first dispatched Mother Jones to the New River coal field in 1897, and she came back to West Virginia in 1902 to join a labor conflict that involved some 16,000 coal miners. At New River, Mother Jones established local unions in Thayer and Mount Hope, but the overall effort achieved relatively little. Several miners were killed by law enforcement and mine guards, and many labor organizers, including Mother Jones, were arrested on dubious charges. U.S. District Attorney Reese Blizzard called her “the most dangerous woman in America” for her ability to mobilize workers against their employers, but she received only a suspended sentence.

A Mine of Ideas

Tensions rose again in the spring of 1912 when mine operators on Paint Creek, some 15 miles northwest of New River Gorge, rejected miners’ demands for small raises, refused to recognize the unions, and hired strikebreakers and more armed guards. Mother Jones was scheduled to give speeches out West, but as soon as she heard of the strikes, she gathered her possessions in a black shawl and hopped on a train. This time, the battle promised to be even fiercer, and many miners took up arms to protect themselves from the owners’ gunmen. In September, the state’s governor declared martial law and authorized military courts. In February 1913, exchanges of shots between miners and a posse assembled by a mine operator resulted in several casualties, including a miner killed in his tent. Miners retaliated a couple of days later by killing mine guards. Only miners were arrested, and when Mother Jones and others protested, they too were taken into custody and charged with murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Mother Jones was allowed to send letters, give interviews and even go out — under escort — to buy beer, but the charges were serious. If convicted, she faced the death penalty. Still, she defiantly refused to recognize the legitimacy of the court and vowed to continue fighting for the miners.

“I am 80 years old, and I haven’t long to live anyhow,” she told The New York Times that March, exaggerating her age by a few years for effect. “Since I have to die, I would rather die for the cause to which I have given so much of my life.”

Her allies mounted a campaign to set her and the other miners free, and she managed to send a telegram to the Senate majority leader asking him to investigate abuse by mine owners. Facing a torrent of bad publicity, West Virginia’s governor freed Mother Jones after nearly three months of incarceration, and mine operators agreed to recognize unions.

“I would count it in my book as a net win on the miners’ side,” said Moore, who is at work on a book about the mine wars.

There wouldn’t be many more such wins. Mother Jones returned to New River in 1917, where she gave a feisty speech comparing local mine barons to the kaiser Americans were fighting in Europe, but her influence was declining. In the culmination of the mine wars, as striking miners clashed violently with law enforcement and strikebreakers at Blair Mountain in southern West Virginia in 1921 — a battle that may have caused as many as 100 deaths — Mother Jones was criticized for trying to restrain the miners and appearing to side with the governor. In the meantime, John L. Lewis, a man she viewed as self-interested, took the helm of the United Mine Workers, and she was further marginalized. She published her autobiography in 1925 and died five years later in Hyattsville, Maryland.

This video of Mother Jones was taken during the last year of her life. Biographers believe she overestimated her age by a number of years, so she is likely in her 90s here.

After booming in the early 20th century, coal production in the New River coal field peaked again in the late 1940s, but it pretty much stopped in the decades that followed. In the late 1960s, outdoor enthusiasts and others started pushing for the protection of the river, which was designated a national river in 1978 and redesignated as a national park and preserve late last year. The slopes, which had once been stripped bare by miners and loggers, are again covered in forests. “Because these areas have been left alone, it has allowed the landscape to come back,” said Eve West, the park’s chief of interpretation. Even so, remnants of the gorge’s industrial past, from lodging to cemeteries and mining equipment, are scattered throughout the park.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Today, Mother Jones magazine can readily be found on newsstands, but many people don’t know anything about the woman it is named after. And few memorials have been built to honor her legacy besides a granite monument on her grave in Mount Olive, Illinois, and a clear plastic panel at the Department of Labor in Washington, D.C. Gorn, Rosemary Feurer, a labor history professor at Northern Illinois University, and many others want to add their own tribute. They are pushing for a statue of Mother Jones to be erected in downtown Chicago, where her labor career began. The point, they say, is to honor the memory of a major labor figure, but also to remind everyone that it took others’ courage and tenacity to obtain protections and benefits many take for granted today, including the 40-hour work week and workplace safety regulations.

“When we remember her,” Feurer said, “we also remember all these people who fought for basic decency.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He writes and edits online content for NPCA and serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.

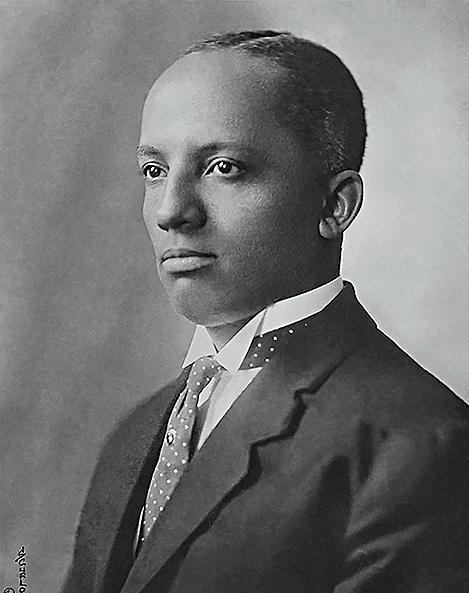

Long before Carter G. Woodson became known as the “father of Black history,” he was working as a young man during the 1890s at the Nuttallburg coal mine, located in what is now New River Gorge National Park and Preserve. While there, he befriended Oliver Jones, a Black Civil War veteran and miner who operated a tearoom and sold sweets out of his house. Jones had assembled an extensive collection of books about Black historical figures and subscribed to several Black newspapers, but he didn’t know how to read or write. “When he heard that Carter G. Woodson could read, he hired him to read to Black miners in exchange for ice cream,” said Catherine Moore, who has researched the role of minority groups in West Virginia coal mines. Woodson not only broadened his knowledge of current affairs and history, but he also got to meet the Black intellectuals who would visit Jones regularly. “In this circle the history of the race was discussed frequently,” Woodson wrote in an essay published in 1944, “and my interest in penetrating the past of my people was deepened and intensified.”

Long before Carter G. Woodson became known as the “father of Black history,” he was working as a young man during the 1890s at the Nuttallburg coal mine, located in what is now New River Gorge National Park and Preserve. While there, he befriended Oliver Jones, a Black Civil War veteran and miner who operated a tearoom and sold sweets out of his house. Jones had assembled an extensive collection of books about Black historical figures and subscribed to several Black newspapers, but he didn’t know how to read or write. “When he heard that Carter G. Woodson could read, he hired him to read to Black miners in exchange for ice cream,” said Catherine Moore, who has researched the role of minority groups in West Virginia coal mines. Woodson not only broadened his knowledge of current affairs and history, but he also got to meet the Black intellectuals who would visit Jones regularly. “In this circle the history of the race was discussed frequently,” Woodson wrote in an essay published in 1944, “and my interest in penetrating the past of my people was deepened and intensified.”