It was a typical San Francisco winter day—in other words, we couldn’t see farther than a car’s length ahead of us—as my family and I drove across the Golden Gate Bridge. The fog horns were blowing, reminding my mom of how, as a child, she’d look out across the San Francisco Bay shrouded in mist and get a chill down her spine thinking of the criminals living out on Alcatraz. We were on our way to that former federal prison—now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area—an eerie place to match the eerie day.

We took the slow, quiet ferry ride across the bay not for the standard jailhouse tour, but to see @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz, a new art exhibit by Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. Ai is internationally known for his work in many mediums that blurs the line between art and activism. Arrested and jailed for alleged economic crimes, Ai is an outspoken critic of the Chinese government and has been prohibited from leaving China since his release from prison in 2011. The FOR-SITE Foundation, a group promoting place-based art, worked in partnership with the National Park Service and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy to install works in and around the jailhouse buildings based on detailed instructions from the artist.

The exhibit unfolds in four different locations on the island, three of which are normally closed off to visitors. A vibrant Chinese dragon—with quotes from famous dissenters etched in its “scales”—snakes through one room. Another room features an installation made of Legos—a colorful and playful contrast to the drab, cold, and foreboding feel of the prison cells. The “A Block” set of cells, normally inaccessible to visitors, features sound recordings of songs, speeches, and chants in the voices of people throughout history who have been detained or otherwise prohibited from exercising free speech. You can sit in the cells and hear Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic voice inspiring nonviolent protest or the songs of Pussy Riot, a Russian punk rock group that gained worldwide attention when three of its members were imprisoned after expressing public opposition to President Vladimir Putin.

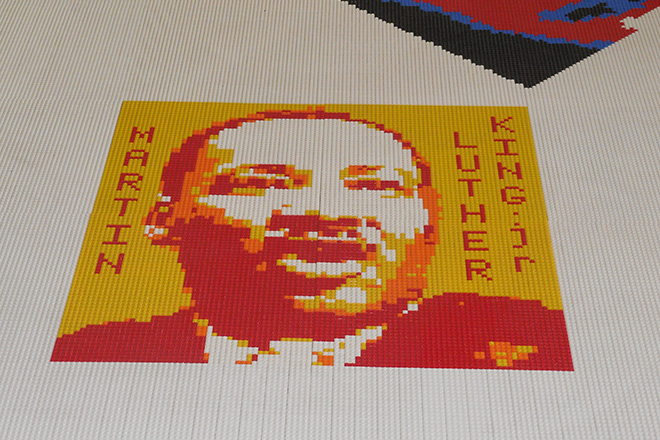

The main installation of the exhibition is 176 portraits of people from around the world who have been imprisoned or exiled because of their beliefs or affiliations since the 1960s. Labeled prisoners of conscience, the portraits range from Edward Snowden, the American former employee of the CIA and NSA that disclosed thousands of classified documents and is currently hiding in Russia, to Aung San Suu Kyi, a Burmese woman who was the chairperson of the National League for Democracy and has been under house arrest since 1990. Ai created the portraits with Legos, making the images unexpectedly bright and colorful. The portraits are displayed on the floor of a large, barren room—a former factory for Alcatraz prisoners—and not up on the wall where viewers would expect to see works of art.

The exhibit is by all accounts thought-provoking. I couldn’t believe why some of the profiled individuals had been or were being held and appreciated learning about their stories. But I also found a disconnect between the ideas the exhibit represents and the stories of the Alcatraz prisoners that once lived on the island. The prisoners at Alcatraz were held for violent crimes—burglary, murder, and breaking and entering, among others. Why use this space to delve into the theme of freedom of speech? Why not place the exhibit on the University of California-Berkeley campus where the Free Speech movement was born and thrived?

I think what shocked me most about the exhibit was the use of Legos. They gave the exhibition a playful and cheery tone. Is that the right emotional context for exploring the denial of personal freedoms? I think the Legos cheapen the messages and legacy of those depicted and are an inappropriate way to honor their lives and work.

Using the prison as a backdrop for the exhibit is meaningful; it helps the visitor understand what life could be like if your basic freedoms were taken away and you were jailed for exercising those freedoms. But Alcatraz is so much more than just the remnants of a federal prison—it was a military fortress for the defense of the Bay Area, a site of Native American heritage and protest, the location of the first lighthouse on the West Coast, and it continues to be one of the premiere viewing locations for colonial nesting seabirds. I’m not convinced that placing these works of art on Alcatraz was the best way to represent what the island is and has been.

The exhibit sparks a range of reactions from viewers—I know because on the ferry ride back to San Francisco, each of us had a differing opinion about the meaning and effects of the artwork, and each defended that opinion with gusto.

Maybe that was the reason why Alcatraz hosted this exhibit—to get visitors talking and interacting with living history.

About the exhibit: @Large: Ai WeiWei on Alcatraz is on display through April 26, 2015 and is free to visit when purchasing a ticket to Alcatraz. The exhibit was commissioned by the FOR-SITE Foundation in partnership with the National Park Service and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. No federal funding was used to commission this work.

Learn more in National Parks magazine.

About the author

-

Natalie Levine Climate and Conservation Program Manager.

Natalie Levine Climate and Conservation Program Manager.Natalie works on a variety of issues including landscape conservation and protection, air quality and visibility, and wildlife protection, with a focus on western states.