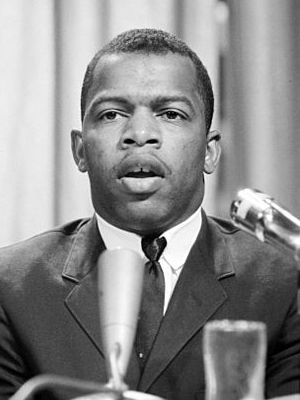

On March 7, 1965, courage and villainy collided on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, when John Lewis and more than 500 other peaceful protesters marched for their constitutional right to vote.

Almost 50 years ago, these demonstrators began forging a trail toward Montgomery that is now memorialized as a national park site—the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail. They only made it six blocks to the foot of the bridge that day before a wall of armed policemen viciously attacked them with tear gas and nightsticks.

I was in my 20s then, watching the newscast on a 12-inch black-and-white TV, tears of rage streaming down my face. Thousands of people like me watched as John Lewis and his fellow protestors showed courage in the face of violence. Their blood became an indelible mark in the building of our nation.

At that time, young Lewis was a chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He had already participated in the 1961 Freedom Rides, helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, and suffered 24 arrests in his demonstrations for civil rights. That day, as he approached the Pettus Bridge, he endured a brutal assault by white lawmen sworn to uphold the law. Severely beaten in the head, he became an icon pressing this country to embrace its higher ideals of justice, fairness, and equality.

To be honest, when I saw those images of violence, I wanted revenge—a feeling many of us from that era are hesitant to acknowledge. Malcolm X’s espousal of “freedom, justice, and equality by any means necessary” seemed like common sense.

As an attorney, I represented black police officers challenging the practices of a segregated police force in St. Petersburg, Florida, and fought for the rights of sanitation workers whose lives and work were made miserable by poor working conditions and constant racial harassment. Yet it took events like “Bloody Sunday” to trigger national outrage.

People around the world watched the events unfold on television. Newspapers and news magazines published photographs on their front pages of organizer Amelia Boynton beaten unconscious. Americans, including President Lyndon Johnson, confronted—and denounced—the brutality they saw.

It took three attempts before demonstrators would cross the Pettus Bridge, but on March 25, a movement of peaceful protestors 25,000 strong finally arrived in Montgomery under federal protection. Less than five months later, Congress passed the landmark federal Voting Rights Act preventing race-based voter discrimination.

I am sure the young civil rights activist John Lewis rejoiced at the passage of the act, as I did.

It may not be the same kind of “revenge” I once imagined, but voters—including ones enfranchised by the Voting Rights Act of 1965—elected John Lewis to the Atlanta City Council in 1981 and to the House of Representatives in 1986. He has been re-elected to his congressional seat nine times and continues to push for equality and justice, as well as the protection of our national parks, forests, and wild places.

Though I hesitate to compare myself to Congressman Lewis, I relate to him. We were both born in southeast Alabama about 50 miles apart—he in 1940 in Troy and me in Henry County in 1937. I now wonder if, on one of my many childhood trips to Troy, I might have driven past young Lewis in his backyard, preaching to the chickens as he often did.

Our paths finally did cross in Atlanta when The Wilderness Society hired me as director of their Southeast Regional Office in 2003. We lived in his congressional district and, after co-founding Keeping It Wild, a non-profit connecting urban citizens to our natural treasures in nearby parks and forests, I invited the congressman to be our first anniversary banquet keynote speaker. Now we jokingly refer to our common Alabama roots whenever we meet.

The Bible says “…faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” In 1965, Lewis stepped out on faith believing that Americans would support what was right and fair and just. Fifty years later, he still holds that faith.

Thankfully, so do I.

About the author

-

Frank Peterman Cofounder and Senior Business Manager for the Diverse Environmental Leaders National Speakers Bureau

Frank Peterman Cofounder and Senior Business Manager for the Diverse Environmental Leaders National Speakers BureauFrank Peterman is cofounder and senior business manager for the Diverse Environmental Leaders National Speakers Bureau and coauthor of Legacy on the Land. He served as Southeast Regional Director of the Wilderness Society from 2003 to 2010 and developed the non-profit Keeping It Wild, which organized educational and recreational visits to the parks and forests. He worked successfully with Congress and conservation organizations to get national park designation for Ocmulgee National Monument and to protect wilderness areas in the North Georgia Mountains. A lifelong nature lover, he recently completed his semi-autobiographical novel, South Florida Son, centered on his youthful experiences related to the breach of the Everglades ecosystem and the development of the Civil Rights movement.

-

General